Cytidine deaminases catalyze the conversion of cytidine to uridine in nucleic acids, a process that can drive extensive mutagenesis. While this activity is beneficial during antiviral immune responses, uncontrolled deamination can damage host genomic DNA and thereby promote cancer. In humans, seven members of the APOBEC3 (A3) family of cytidine deaminases have been linked either to antiviral defense or to cancer-associated mutagenesis. In their new study, the Versteeg lab identifies the ubiquitin–proteasome system as a key pathway for selectively degrading cancer-associated A3 proteins, while the cell protects antiviral A3 enzymes from degradation, thereby addressing the fundamental challenge of controlling ‘DNA hypermutators’ that are both essential for immunity and potentially harmful to genomic integrity.

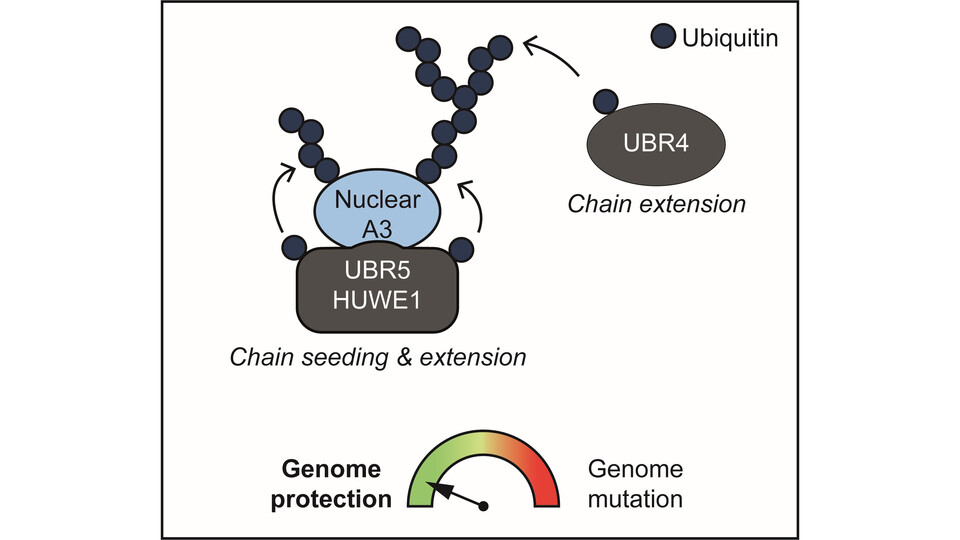

Using CRISPR–Cas9 genetic screens combined with proteomics, the researchers identified specific E3 ubiquitin ligases that selectively target unstable, cancer-linked A3 proteins for degradation. Loss of the three ligases UBR4, UBR5, and HUWE1 led to the accumulation of cancer-associated A3 proteins and was associated with increased genomic hypermutation. This work reveals a previously unappreciated layer of post-translational regulation of A3 protein levels, as first author Valentina Budroni explains: “In our study, we were able to show that UBR5 and HUWE1 specifically bind to the non-RNA-bound A3 proteins in the nucleus.” In contrast, cytosolic A3 proteins – critical for antiviral defense – were not targeted for degradation, ensuring their sustained availability during the antiviral immune response.

A central conceptual advance of the study is the demonstration that RNA binding acts as a molecular ‘zip code’ for A3 proteins, determining both their localization and fate. As group leader Gijs Versteeg explains: “When bound to RNA, A3 enzymes are retained in the cytosol, where they support antiviral defense and are kept away from genomic DNA in the nucleus.” Reduced RNA binding, by contrast, allows a fraction of A3 proteins to enter the nucleus, where they pose a mutagenic threat and are selectively targeted for degradation to protect genomic integrity. Emphasizing the broader implications, first author Irene Schwartz adds: “Cells may use this RNA-based protection mechanism more broadly, such that dissociation from RNA serves as a signal to trigger the degradation of other RNA-binding proteins”, a potentially promising future research direction for the Versteeg lab.

Medically, the findings suggest the intriguing possibility that dysregulation of protein turnover could contribute to APOBEC mutation signatures observed in many cancers. By highlighting protein-level regulation and proteasomal pathways as critical but previously overlooked contributors to cancer-associated mutagenesis, the study also suggests broader relevance for other RNA- and DNA-binding proteins. The work was made possible through collaborations with experts from different fields, including key contributions from the Karagöz lab, as well as the Clausen and Haselbach labs (IMP), which provided essential biochemical and in vitro reconstitution expertise. Mathilde Meyenberg from the Menche lab played a central role in the bioinformatics analyses and data integrating mutations in, or deletions of, E3 ligases with cancer-associated APOBEC3 mutation patterns.

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-026-68420-5